Most reliable "best" radio

-

@NeverDie A young Scott Harden taught me, via Youtube how to use a soundcard and Audacity recording SW as an o'scope. He would transmit a known preamble followed by a known pattern. I think this can be done in OSK, FSK, OOK. When the data is in Audacity, or an o'scope, then you can take your time to learn the timing of the transmitted and received signal. Seeing is believing, for me.

@Larson Although I haven't tried it myself, I have my doubts that a soundcard would work for recording signals sent at 2mbps, if only because that is way outside the spec for normal sound recordings. However, for slow signals, yes, I can believe it would work.

There are also software defined radio receivers that would probably do a good job of receiving and, with the right software, displaying signals. Certainly HackRF One would be one such device that could do it. I haven't tried that either, but it was designed for the purpose. IIRC, Andreis Speiss did a video on using a cheap ($10-$20) SDR to receive and decode some fairly basic radio packets. Maybe it would display them as well.

-

@Larson Although I haven't tried it myself, I have my doubts that a soundcard would work for recording signals sent at 2mbps, if only because that is way outside the spec for normal sound recordings. However, for slow signals, yes, I can believe it would work.

There are also software defined radio receivers that would probably do a good job of receiving and, with the right software, displaying signals. Certainly HackRF One would be one such device that could do it. I haven't tried that either, but it was designed for the purpose. IIRC, Andreis Speiss did a video on using a cheap ($10-$20) SDR to receive and decode some fairly basic radio packets. Maybe it would display them as well.

@NeverDie If I remember correctly, I was working on 433 MHz radios at the time - so a little slower rate. The sampling rate available though Audacity was way more than I needed to see the digital signal. At the time it was my first introduction to digital radio. And, in life so often, the first experience is the best. And it helped me realize that more advanced SW/HW like the PPKII depend on the same sampling of a signal. Pretty danged cool.

-

@NeverDie If I remember correctly, I was working on 433 MHz radios at the time - so a little slower rate. The sampling rate available though Audacity was way more than I needed to see the digital signal. At the time it was my first introduction to digital radio. And, in life so often, the first experience is the best. And it helped me realize that more advanced SW/HW like the PPKII depend on the same sampling of a signal. Pretty danged cool.

@Larson About 10 years ago I did it using the A2D on an Arduino Due once for a simple 433Mhz OOK receiver. It worked well enough. Like you, it was my first experience doing such things. The hardware was so basic that it was a software-only radio from the mac layer up. The Due was fast enough that I could detect both the original signal (shortest path) and subsequent bounced signals (multipath) as separate entities. I still think it's pretty cool. :sunglasses:

-

@Larson About 10 years ago I did it using the A2D on an Arduino Due once for a simple 433Mhz OOK receiver. It worked well enough. Like you, it was my first experience doing such things. The hardware was so basic that it was a software-only radio from the mac layer up. The Due was fast enough that I could detect both the original signal (shortest path) and subsequent bounced signals (multipath) as separate entities. I still think it's pretty cool. :sunglasses:

-

@Larson About 10 years ago I did it using the A2D on an Arduino Due once for a simple 433Mhz OOK receiver. It worked well enough. Like you, it was my first experience doing such things. The hardware was so basic that it was a software-only radio from the mac layer up. The Due was fast enough that I could detect both the original signal (shortest path) and subsequent bounced signals (multipath) as separate entities. I still think it's pretty cool. :sunglasses:

@NeverDie

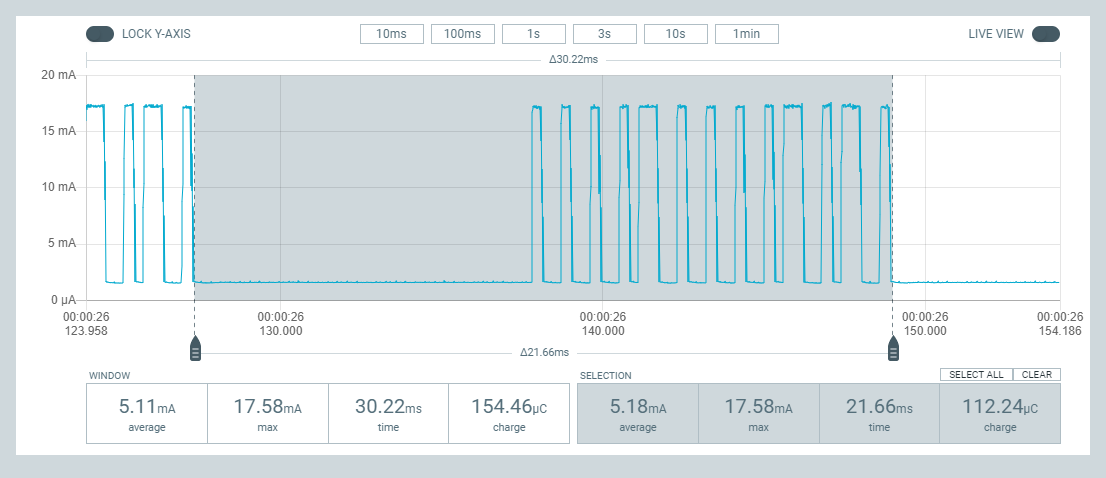

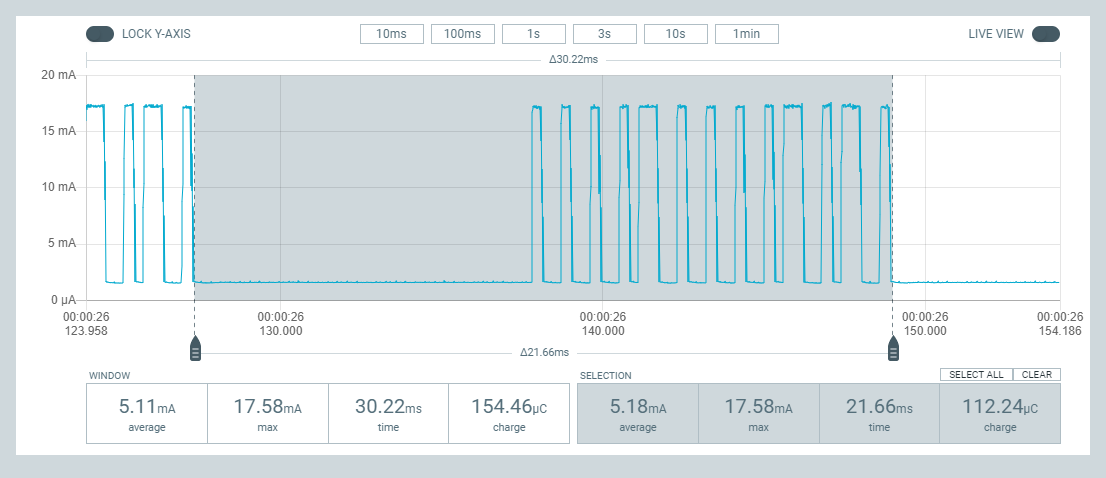

Here is a view of what the Power Profiler Kit II sampler (100,000 samples/second) could see. This is my 433 MHz radio/motion-detector rig picking up motion and sending a HT12E 12-bit address/data byte. Really fun to see that the ones and the zeros can be clearly seen in the FSK profile of the measured current of the device.

Here is a view of what the Power Profiler Kit II sampler (100,000 samples/second) could see. This is my 433 MHz radio/motion-detector rig picking up motion and sending a HT12E 12-bit address/data byte. Really fun to see that the ones and the zeros can be clearly seen in the FSK profile of the measured current of the device. -

@NeverDie

Here is a view of what the Power Profiler Kit II sampler (100,000 samples/second) could see. This is my 433 MHz radio/motion-detector rig picking up motion and sending a HT12E 12-bit address/data byte. Really fun to see that the ones and the zeros can be clearly seen in the FSK profile of the measured current of the device.

Here is a view of what the Power Profiler Kit II sampler (100,000 samples/second) could see. This is my 433 MHz radio/motion-detector rig picking up motion and sending a HT12E 12-bit address/data byte. Really fun to see that the ones and the zeros can be clearly seen in the FSK profile of the measured current of the device.@Larson That's pretty cool. I suppose if it were OOK, you wouldn't even need a receiver to see the contents of a transmitted packet. You could maybe check your garage door opener or one of the cheaper TH sensors. Or check an IR transmitter to see what pattern it's sending.

-

@Larson That's pretty cool. I suppose if it were OOK, you wouldn't even need a receiver to see the contents of a transmitted packet. You could maybe check your garage door opener or one of the cheaper TH sensors. Or check an IR transmitter to see what pattern it's sending.

@NeverDie Excellent thinking on the signal detection. I think I'm going to build a garage door repeater. While the signal probably has some kind of encryption, maybe all I need to do is to repeat the same signal. But before I do that, I’ve got to return to the radio project you inspired. Elder-care has all of my time for now.

My description above was a bit cryptic. What I marvel at is that I was only measuring the device power and didn’t know the transmitted code would be revealed in the power profile. But that makes sense now for most any battery powered transmitter including OOK, ASK protocols. As such your thought about detecting codes from TV remotes to garage doors would apply just by measuring the power battery power to the device. Effectively the PPKII becomes an O’scope. -

@NeverDie Excellent thinking on the signal detection. I think I'm going to build a garage door repeater. While the signal probably has some kind of encryption, maybe all I need to do is to repeat the same signal. But before I do that, I’ve got to return to the radio project you inspired. Elder-care has all of my time for now.

My description above was a bit cryptic. What I marvel at is that I was only measuring the device power and didn’t know the transmitted code would be revealed in the power profile. But that makes sense now for most any battery powered transmitter including OOK, ASK protocols. As such your thought about detecting codes from TV remotes to garage doors would apply just by measuring the power battery power to the device. Effectively the PPKII becomes an O’scope.@Larson Unless you have a really ancient garage door remote, your garage remote most likely uses some kind of rolling code that's intended to prevent a simple playback attack. Unless you happen to know the packet/frame layout, and probably the algorithm as well, then reverse engineering it can be quite time consuming. I once did it for a consumer soil moisture sensor, and it was damn hard. Reading the bits wasn't hard, but figuring out the semantics represented by those bits took quite a bit of effort--way more than it was worth, as I subsequently discovered the sensor didn't have good accuracy in the first place. A bit ironic, as there was no way to discover that until after I had the detailed data that had previously been inaccessible.

-

@Larson Unless you have a really ancient garage door remote, your garage remote most likely uses some kind of rolling code that's intended to prevent a simple playback attack. Unless you happen to know the packet/frame layout, and probably the algorithm as well, then reverse engineering it can be quite time consuming. I once did it for a consumer soil moisture sensor, and it was damn hard. Reading the bits wasn't hard, but figuring out the semantics represented by those bits took quite a bit of effort--way more than it was worth, as I subsequently discovered the sensor didn't have good accuracy in the first place. A bit ironic, as there was no way to discover that until after I had the detailed data that had previously been inaccessible.

@NeverDie said in Most reliable "best" radio:

your garage remote most likely uses some kind of rolling code

Yep, that's me. I figured the relay/repeater would echo the same rolling code in-and-out without having to figure it out. I've got enough earthly bound problems that are hard enough, so I'll take your advice and spend my festering curiosity on something more productive. But still ths PPKII is pretty danged cool.

-

@NeverDie said in Most reliable "best" radio:

your garage remote most likely uses some kind of rolling code

Yep, that's me. I figured the relay/repeater would echo the same rolling code in-and-out without having to figure it out. I've got enough earthly bound problems that are hard enough, so I'll take your advice and spend my festering curiosity on something more productive. But still ths PPKII is pretty danged cool.

-

@Larson What all does the elder care entail? If it's just supervision, maybe you can provide it using your automation skills. Obviously, something better than merely, "I've fallen down and can't get up!"

@NeverDie said in Most reliable "best" radio:

What all does the elder care entail? If it's just supervision, maybe you can provide it using your automation skills.

Thanks for asking. Yea, I thought of assigning a robot to the task of caring for my mother, but then I would be cast to the dungeon of my own making. Broken-hip, surgery, Rehab, Discharge - it is complicated and demanding. Fortunately we have skilled nursing and CNA's to do the bulk of the hard work. But getting mom's 'extended' taxes done, pain management intervention, arranging for PT, OT, Surgeon follow-up, rehab facility discharge, hemotologists, PCP's and where to land... it is a full time job. And then there is emotional support visits for the patient, my mom, while stress among sibilings and spouses becomes damaging. We all live too long.

Yea, programming radios is my relief: develop, test, then correct. Far less human, and far more certain and way more fun. And when you are done for the day... you simply go to sleep. Sweet!

I've been rereading this thread this evening. I'm glad for the record as I can relearn - even from myslef. So many great ideas that need further work by me. My 433 ASK transmitters are now controlled by 328P chips because the transmit times can be limited to 200 mS at about 6mA. I know, some of your radios can transmit faster but I'm just now divorcing my HT12E and HT12D chips and that is going to take time. Baby steps.

On my new config (Barebones/SR501 motion detector/433 transmitor, the sleep current seems to be about 62 uA and that supports the SR501 motion detectors. That power dominates the energy profile of the device and is near the shelf-discharge of the battery - so it doesn't deserve much study. But the speed of the radio transmission does warrent further study since that is the high current period.

-

It has been a long time but I’ve learned a few things that I wanted to share.

- This library of information (Thank you NeverDie and others) has been so helpful in my hobby developments.

- Software Defined Radios for signal analysis. With the help of Andreas Spiess explanation of IQ transformations, I learned about Software Defined Radios and I bought one (RTL-SDR). Using this I can clearly discriminate between effective 433 MHz transmitters and bad ones. Not only is the signal density displayed on the software (SDR#) but so is the frequency.

- Power Profiler Kit II has been indispensable in watching power usage and seeing into the details of the radio transmission. In effect this thing has saved me from buying an oscilloscope for my simple little bench.

- Tonight, I saw this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z9nycymUd-I It describes common PCB errors. It is too advanced for me, but I did pick-up a few ideas about ground planes (tip #6 from the video).

I hope this is of some value for folks.